Five portions of fruit and vegetables a day – a familiar mantra for those concerned about their own and their children's health – may not, after all, be enough, according to a new report by scientists, who suggest we should instead be aiming for seven a day, and mostly vegetables at that.

Good fruit, bad fruit

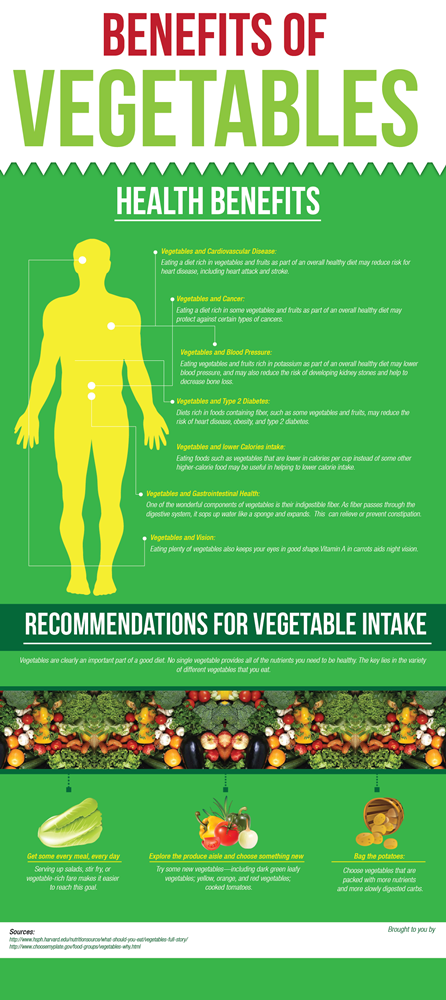

Examining the eating habits of 65,000 people in England between 2001 and 2013, the researchers from University College London (UCL) found that people who ate seven or more portions daily had a 42% reduced risk of death overall compared to those who managed just one. Boosting consumption was also associated with a 25% lower risk of cancer and 31% lower risk of heart disease or stroke.

Fresh vegetables were found to have the strongest protective effect, followed by salad and then fruit. Two to three daily portions of vegetables resulted in a 19% lower risk of death among those studied, compared with 10% for the equivalent amount of fruit. Overall, vegetables pack more of a protective punch than fruit, the authors said.

There was a surprise finding: people who ate canned or frozen fruit actually had a higher risk - 17% - of heart disease, stroke and cancer.

The authors, Dr Oyinlola Oyebode and colleagues from the department of epidemiology and public health at UCL, said they were unsure how to interpret the findings on canned or frozen fruit. It could be that people eating canned fruit may not live in areas where there is fresh fruit in the shops, which could indicate a poorer diet.

Alternatively, they could be people who are already in ill-health or they could lead hectic lifestyles. There is also another possibility: frozen and tinned fruit were grouped together in the questions, but while frozen fruit is considered to be nutritionally the same as fresh, tinned fruit is stored in syrup containing extra sugar. More work needs to be done to see whether sweetened, tinned fruit is in fact the issue, the researchers say.

Why these findings are interesting

Oyebode and colleagues took into account the socio-economic background, smoking habits and other lifestyle factors that affect people's health. What they have found, they say, is a strong association between high levels of fruit and vegetable consumption and lower premature death rates – not a causal relationship.

But the strength of the study, published in the Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, is in the big numbers and the fact that the data comes from the real world – not a collection of individuals who had a particular health condition or occupation, but a random selection.

Can policy changes encourage us to eat more fruit and veggies?

The study calls for the 5-a-day message based on World Health Organisation guidance to be revised upwards, and possibly exclude portions of dried and tinned fruit, smoothies and fruit juice which contain large amounts of sugar.

Other experts agreed that the study was sound and representative of the population, but cautioned that in a study of the habits of people in the real world, it is hard to take full account of complications, such as education, smoking habits and people failing to tell the exact truth about their diet.

They say it is too early to change the current 5-a-day message to seven or more a day on the basis of this study. Considering that most people do not achieve the 5-a-day target, experts believe moving the goalposts to 7-a-day will deter people from even trying to eat a healthier diet.

They say current efforts will therefore be better spent in getting the population intake to meet the guideline of eating at least 5-a-day, which offers a win-win for all.

Bottom line

"The clear message here is that the more fruit and vegetables you eat, the less likely you are to die at any age. Vegetables have a larger effect than fruit, but fruit still makes a real difference.

However, people shouldn't feel daunted by a big target like seven. Whatever your starting point, it is always worth eating more fruit and vegetables.

In our study even those eating one to three portions had a significantly lower risk than those eating less than one." concluded Dr Oyinlola Oyebode.

Sources: http://www.ucl.ac.uk/news/, http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/, http://www.newscientist.com/, http://www.theguardian.com/, http://www.independent.co.uk/, http://www.dailymail.co.uk/